Distance is defined by points ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

| (6.14) |

| (6.15) |

The first derivatives of ![]() with respect to Cartesian coordinates are:

with respect to Cartesian coordinates are:

| (6.16) | |||

| (6.17) |

Angle is defined by points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , and spanned by vectors

, and spanned by vectors

![]() and

and ![]() :

:

| (6.18) |

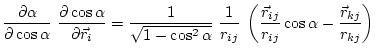

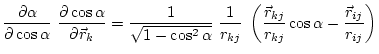

The first derivatives of ![]() with respect to Cartesian coordinates are:

with respect to Cartesian coordinates are:

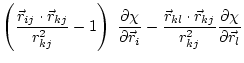

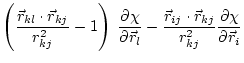

|

(6.19) | ||

|

(6.20) | ||

|

(6.21) |

These equations for the derivatives have a numerical instability when

the angle goes to 0 or to 180![]() .

Presently, the problem is `solved' by testing for the size

of the angle; if it is too small, the derivatives are set to 0

in the hope that other restraints will eventually pull the angle

towards well behaved regions. Thus, angle restraints of 0 or

180

.

Presently, the problem is `solved' by testing for the size

of the angle; if it is too small, the derivatives are set to 0

in the hope that other restraints will eventually pull the angle

towards well behaved regions. Thus, angle restraints of 0 or

180![]() should not be used in the conjugate gradients or molecular dynamics

optimizations.

should not be used in the conjugate gradients or molecular dynamics

optimizations.

Dihedral angle is defined by points ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() (

(![]() ):

):

| (6.22) |

| (6.23) |

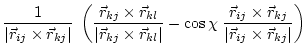

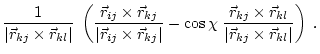

The first derivatives of ![]() with respect to Cartesian coordinates are:

with respect to Cartesian coordinates are:

| (6.24) |

| (6.25) |

|

(6.26) | ||

|

(6.27) | ||

|

(6.28) | ||

|

(6.29) | ||

|

(6.30) | ||

|

(6.31) |

These equations for the derivatives have a numerical instability when the angle goes to 0. Thus, the following set of equations is used instead [van Schaik et al., 1993]:

| (6.32) | |||

| (6.33) | |||

| (6.34) | |||

| (6.35) | |||

|

(6.36) | ||

|

(6.37) |

The only possible instability in these equations is when the length of

the central bond of the dihedral, ![]() , goes to 0. In such a case,

which should not happen, the derivatives are set to 0. The expressions for

an improper dihedral angle, as opposed to a dihedral or dihedral angle,

are the same, except that indices

, goes to 0. In such a case,

which should not happen, the derivatives are set to 0. The expressions for

an improper dihedral angle, as opposed to a dihedral or dihedral angle,

are the same, except that indices ![]() are permuted to

are permuted to ![]() .

In both cases, covalent bonds

.

In both cases, covalent bonds ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are defining

the angle.

are defining

the angle.

xx

Atomic density for a given atom is simply calculated as the number of atoms within a distance energy_data.contact_shell of that atom. First derivatives are not calculated, and are always returned as 0.

The absolute atomic coordinates ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are available

for every point

are available

for every point ![]() , primarily for use in anchoring points to planes, lines

or points. Their first derivatives with respect to Cartesian coordinates

are of course simply 0 or 1.

, primarily for use in anchoring points to planes, lines

or points. Their first derivatives with respect to Cartesian coordinates

are of course simply 0 or 1.